Flying the World’s Only Lisunov Li-2!

Introduction

Once in a while during Hungary’s warmer months, the distinctive noisy growl that could only be produced by radial piston engines fills the skies of Budapest. Below, tourists are temporarily distracted from the famous grandeur of the Hungarian capital as a vintage propliner rumbles overhead, making several passes before fading off towards the city’s suburbs. Whilst even those with little interest in aviation may recognise that the aircraft is far from your typical Airbus or Boeing, few will grasp the extraordinary rarity of this old propliner – the world’s only airworthy Lisunov Li-2. Operated by a local band of passionate volunteers, the Goldtimer Foundation, this is no rich person’s accessory. Instead, the aircraft offers enthusiasts and non-enthusiasts alike the opportunity to see the sights of Budapest from the vantage point of a well-preserved flying museum piece.

History of the Li-2

Perhaps the first impression of many who see the Lisunov Li-2 is its uncanny resemblance to the famous Douglas DC-3. Indeed, unless you are one of the few who happen to be a connoisseur on the intricacies of the Lisunov Li-2, ignoring liveries, it is unlikely that you will be able to tell the two apart with most dissimilarities between the two aircraft being ‘under the bonnet’. Yet while the history of relations between the Soviet Union and United States may be clouded by Cold War hostilities, the Lisunov Li-2 was not a product of international espionage but this emerged through cooperation in a period of relative detente between the two powers.

First taking to the skies in December 1935, it did not take long for the highly popular Douglas DC-3 to join the fleets of airlines across the globe. With Soviet carrier Aeroflot expressing an interest in the type, in a move that would have been unthinkable just a decade later, in July 1936 the American and Soviet governments alongside the Douglas Aircraft Company reached an agreement that would see the type manufactured under licence in the Soviet Union. On a side note, the Soviets were not alone in this endeavour, with a similar agreement drawn up with Japan that resulted in almost five hundred L2Ds produced by manufacturers Nakajima and Showa until the end of the Second World War.

Following the conclusion of this deal, a party of Soviet aerospace engineers directed by Boris Lisunov headed from Moscow to Santa Monica, where they were assigned to the Douglas Aircraft Company’s Californian plant. There, the engineers studied the Douglas DC-3 and eventually proposed over a thousand modifications to optimise the aircraft for the Soviet Union’s harsh climes. These included minor ‘tweaks’ and more notable changes such as the shifting of the main cabin door to the right-hand side of the fuselage and the replacement of the DC-3’s Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9 engines with the locally produced and slightly less powerful Shvetsov ASh-62IR. With the plans and technology in place, the ‘Soviet DC-3’, known initially as the PS-84 rolled off the production line of the State Aviation Factory 84 near Moscow, making its maiden flight in 1939.

Initially intended as a civilian transport aircraft, the Li-2 was soon pressed into service with Aeroflot. However, as with the Douglas DC-3, the outbreak of the Second World War saw the Lisunov undertake a variety of military roles for which it had not been intended. The most common role was, unsurprisingly, as a military transport; however, the Soviet military also utilised the Lisunov in both bombing and reconnaissance roles. With Moscow under threat from bombardment and invasion, in 1941 production of the Lisunov Li-2 migrated eastwards to Central Asia where it was undertaken at the Tashkent Aviation Production Organisation plant. Following the conclusion of the war, manufacture of the Lisunov remained centred in Tashkent, although 353 examples were also manufactured in the Far Eastern city of Komsomolsk-on-Amur between 1947 and 1950.

As the Second World War drew to a close and the Cold War rolled into motion, the political landscape was notably different to that of the 1930s. Nevertheless, the Lisunov proved to be a useful tool in expanding the Soviet sphere of influence, with many exported to the country’s allies where they served in civilian and military roles in fourteen countries across Africa, Asia and Europe. However, the Li-2 became increasingly obsolete as focus shifted towards the development of a more modern, indigenous aircraft type, namely the Ilyushin Il-14. As a result, following a production run of fourteen years, the final Lisunov Li-2 rolled off the production line in 1953.

From the mid-1950s, the situation faced by the Lisunov Li-2 could be argued to mirror that of the Douglas DC-3 in many parts of the world. Just as new modern turboprop aircraft such as the Fokker F27 and Hawker Siddeley HS748 threatened the viability of the DC-3, the Antonov An-24 provided a new challenge to both the Lisunov Li-2 and its successor, the Ilyushin Il-14. Developed to replace both types, Antonov’s new turboprop was capable of carrying higher payloads, further and at greater speeds to and from remote strips throughout the country. Yet, with over four thousand Lisunov Li-2s having taken to the skies, the decline of the type was far from immediate, lingering for several decades in military and utility roles. As the years passed, the Lisunov Li-2 came to fill the aircraft graveyards and museums across the Soviet Union, with many withdrawn from use by the 1970s. In China, the type lasted slightly longer before being retired during the mid-1980s, whilst the final military user of the type is thought to have been North Korea, although their exact date of retirement there is unknown.

About the Goldtimer Foundation

In 1992, a small team of enthusiasts, engineers and pilots led by Károly Hajdu formed the Goldtimer Foundation. Based at Budapest’s historic general aviation hub at Budaörs Airfield, the foundation aimed to preserve, restore and operate a unique selection of rare aircraft. Commemorating Hungary’s aviation heritage, today the foundation operates a replica Bánhidi Gerle as well as one of just nine Rubik R-18 Kánya that were built, plus two rare Rubik gliders – an R-07 Vöcsök and an R-11b Cimbora. These come in addition to a rare 1954 PZL-Okecie CSS-13 (a Polikarpov Po-2 manufactured under licence in Poland). However, despite the rarity of each of these types, the Goldtimer Foundation is unquestionably best known for its operation of the world’s only airworthy Lisunov Li-2.

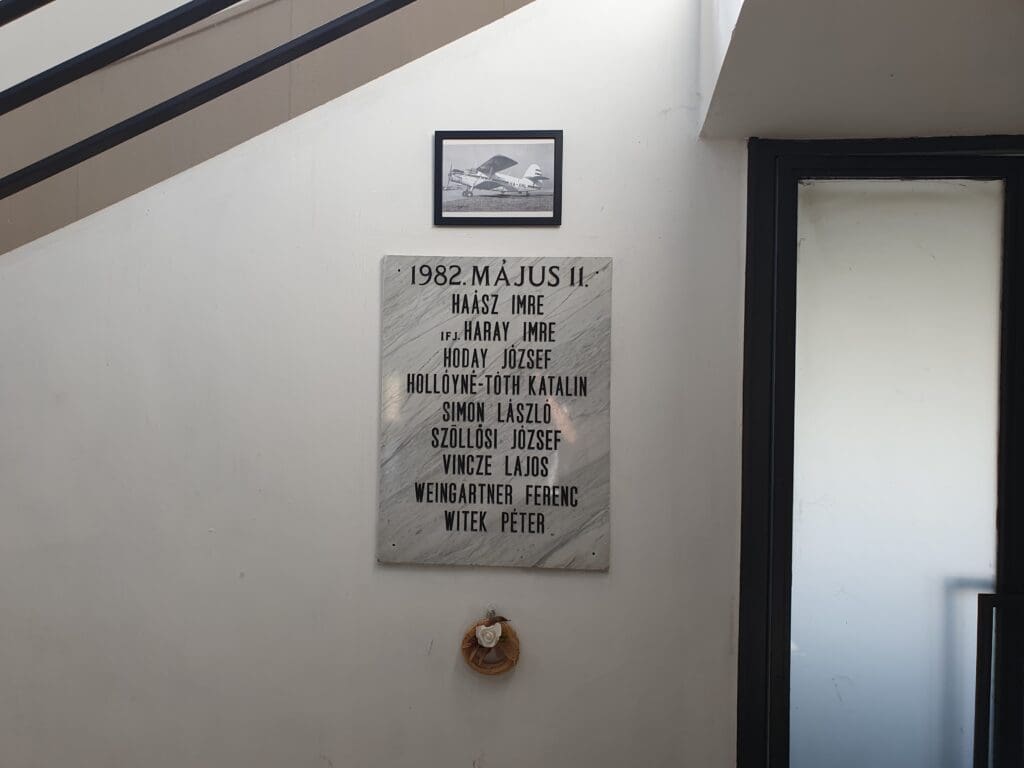

Firmly in the Soviet sphere of influence following the end of the Second World War, in 1946 five Lisunov Li-2s and five Polikarpov Po-2s were exported to Hungary and joined the fleet of Soviet-backed national carrier Maszovlet. In total, 31 Lisunov Li-2s ended up on the Hungarian aircraft register, operating in both civilian and military guises. Commencing their search for a suitable Li-2 to restore to working order a short time after the foundation’s creation, Goldtimer faced multiple hurdles. Despite the number that had ended up in service in Hungary all had been long withdrawn from service, and finding an Li-2 in a suitable state for restoration proved difficult. Finally, in 1997, they came across a long withdrawn yet still salvageable Lisunov Li-2T at the Kilián György Aviation Technical College in the Hungarian city of Szolnok.

Initially thought to have been HA-LIZ, further research revealed this example to be HA-LIX. Manufactured in 1949 by the Tashkent Aviation Production Association, this Lisunov commenced its life in the ranks of the Hungarian People’s Army where it bore the registration 209 and primarily worked as a target tug. Alongside several other Lisunovs, in 1957 the aircraft was transferred to the civilian world where it worked for the national carrier Malév and received its current registration. However, with the airline’s introduction of the four-engined Ilyushin Il-18 turboprop in 1960, the Lisunov became increasingly redundant and was transferred back to the military in 1961. In 1974, HA-LIX was demobilised for good and ended up on display in Szolnok. Upon discovery by the Goldtimer Foundation, with the aircraft having sat stationary for over two decades, it came as little surprise that the aircraft would need very substantial work before taking to the skies again. Fortunately, the Goldtimer Foundation was equal to the challenge and in the summer of 1997 the aircraft was carefully dismantled and transported to Budaörs by road. Once safely in Budaörs, the mammoth task of restoring the Lisunov Li-2 commenced in earnest. On the Goldtimer Foundation’s side was a team of experts and engineers, the support of several aviation companies, and a wealth of documentation regarding HA-LIX and the Lisunov Li-2.

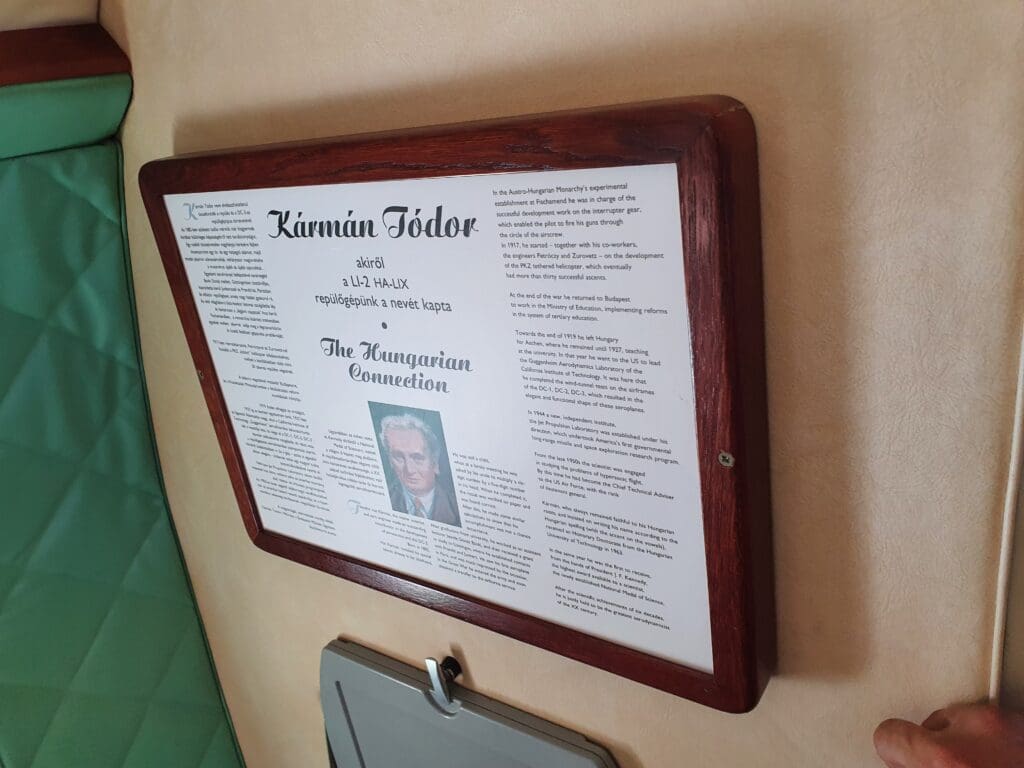

After four years and thirty thousand man hours, in September 2001 a rough and ready unpainted HA-LIX took to the skies for its first flight since 1974 and only a minor series of tweaks was needed before the Hungarian Civil Aviation Authority awarded the aircraft its airworthiness certificate. Painted in the colours of the aviation company Sunflower who had contributed to the Lisunov’s restoration, and christened Tódor Kármán in honour of the famed Hungarian aerospace engineer, the aircraft began to offer pleasure flights. Since then, the aircraft received a vintage Malév livery in 2008 and has popped up at air shows and events across Europe, ranging from small fly-ins to the ILA Berlin Air Show. In June 2019, the aircraft participated in ‘Daks over Normandy’ where it served as a Dakota stunt double and saw a team of parachutists bail out as it rumbled along the Normandy coastline. Today, the aircraft continues to operate sightseeing flights from both Budaörs Airfield and Budapest Airport, with the latter undertaken in partnership with the local aviation museum, the Aeropark.

In August 2022, I fulfilled my duty as a diehard enthusiast and made the pilgrimage to Hungary to fly on the world’s only airworthy Lisunov Li-2. Reserving a seat three months in advance via email, I was advised to appear at the Budaörs Airfield at least thirty minutes before the 30 minute flight’s scheduled departure time of 1030 and advised that I would have to pay the very reasonable 22,000 Ft (£46) in cash upon arriving there. I later also added 15 minute joyrides in the foundation’s replica Bánhidi Gerle and Polikarpov Po-2 aircraft for 30,000 Ft. All set to fly with the Goldtimer Foundation on a Saturday morning, I booked the Friday off work to give me some time to explore the sights of the Hungarian capital. To reach Budapest, I enlisted the help of British Airways and parted with a total of 16,500 miles and £35 for direct return flights from London Heathrow. After booking, whilst three months separated myself from my long weekend in Budapest, my non-stop schedule both in and outside of work ensured that time whizzed by and before I knew it I touched down in Hungary onboard an Airbus A321 full of weekend trippers.

Once through immigration and out of the terminal, my first stop on my weekend away was Budapest Airport’s Aeropark – home to a collection of well-restored rare aircraft that previously played an important role in Hungary’s aviation industry, one such aircraft taking the form of an ex-Malév Lisunov Li-2! With this must-see sight ticked off my list, afterwards I returned to the terminal and took a bus into the city. That afternoon, a combination of my three-hour sleep the previous evening and the boiling hot near-forty degree August weather meant that by the time I reached my Airbnb inside an old apartment building on the down-to-earth street of Népszínház, I was shattered. However, with limited time to explore the city, following a short pause to recharge both myself and my phone, I dragged myself out onto the city’s streets to tour some of Budapest’s famous sights.

My Li-2 Experience

Having had a refreshing sleep despite the boiling temperatures of the non-air-conditioned apartment, I woke up bright and early, raring to head off. Following a quick trip out to grab a coffee from McDonalds (the only café that seemed to be open at that time), I returned to my room and packed everything that I would need for the morning. Whilst the Goldtimer Foundation occasionally offers sightseeing flights in their Lisunov Li-2 propliner from Budapest’s main airport, that day, I would be flying from the foundation’s home at Budaörs Airfield – Budapest’s original airport, located twelve kilometres away from the city centre. That day, my first flight would be a 30-minute jaunt on the Lisunov Li-2 departing at 1030. Having been requested to be at the airfield at least thirty minutes before departure, Citymapper advised that I would not have to leave until 0915. However, not wanting to cut things too fine, I decided to head out onto the quiet morning streets at 0820 and walked the short distance down to Il. János Pál Pápa Tér station, located on Budapest Metro’s Line 4.

Arriving at the station a short time later, already in possession of a still-valid 24-hour ticket, I made my way straight down the escalators to platform level and waited for the next Kelenföld vasútállomás bound train to appear. After a few minutes, a rumbling could be heard and indicators on the platform began to flash before the modern and driverless Alstom Metropolis train rattled into the station. Joining several other Saturday morning passengers, I was soon whisked westwards deep under the streets of Central Budapest towards the Danube. Whilst my journey involved travelling almost the entire length of Line 4, this took no more than about twelve minutes and I soon found myself disembarking at Kelenföld, one of Budapest’s main railway termini. Once there, I headed upwards to street level and made a short walk to the station’s local bus stops. Unfortunately, upon arriving there I found out that I had just missed the number 187 bus, the only service that would take me to the airfield. With this departing at intervals of every thirty minutes, a reasonable wait was in store and so I headed back down into the station in search of a temporary respite from the morning heat. Not wanting to miss the next bus and end up in a taxi, I decided to head back to the bus stop with ten minutes to go until the scheduled departure time, and to my delight, the bus rolled up after no more than a five-minute wait. After showing my 24-hour ticket, I boarded the bus and was soon whisked away towards the airfield.

Following an uneventful 10-minute bus ride, I disembarked with a little over an hour until the departure time of my Lisunov flight. From the bus stop, I made a very short walk along the main road before reaching the airfield’s main gates. Having not been advised on where exactly to rendezvous before departure, I hoped that Budaörs Airport would be small enough to avoid any last-minute frantic search for the right place to be. Indeed, the airfield proved to be compact, consisting of a line of hangars and the old terminal building alongside the usual smorgasbord of airfield buildings. Meanwhile, up ahead, a temporary metal fence could be seen separating the apron from the landside area, beyond which the entirety of the Goldtimer Foundation’s fixed-wing fleet could be seen.

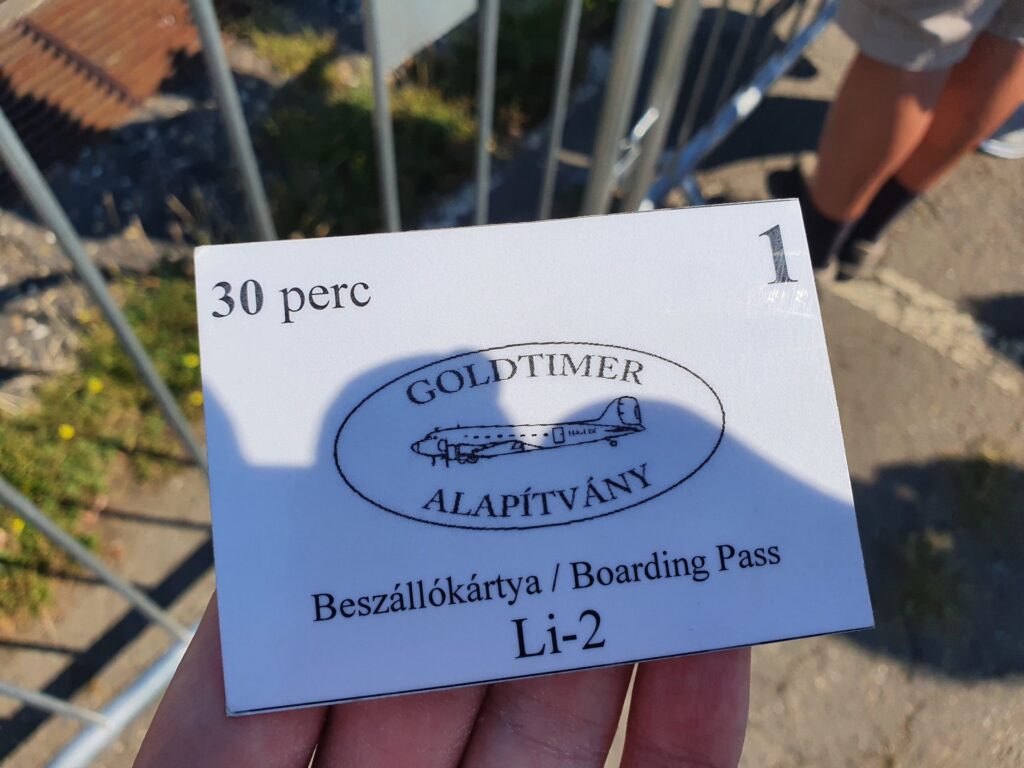

Following several other passengers, I headed in the direction of the Lisunov Li-2 and ended up outside the terminal building where several tables had been set up. There, a host of the Goldtimer Foundation’s volunteers could be seen welcoming passengers and undertaking administrative duties. Upon walking up to the desk, I was given a very friendly greeting in Hungarian by one of the volunteers who then switched to fluent English once they realised I was a foreigner. Being one of just three non-Hungarian passengers on all of the Goldtimer Foundation’s flights that day, the staff seemed to know who I was and I was requested to provide my address, and passport number and give a signature which I assume was for some sort of disclaimer. Once done, I handed over a thick wad containing 84,000 Ft for the three flights and received a small rectangular laminated reusable boarding pass, a Lisunov Li-2 postcard and a handwritten receipt in exchange before being advised to meet at the fence line next to the Li-2 ten minutes before departure.

With around fifty minutes to go until I had to report for duty, I decided to have a wander around the airfield. Having opened in 1937, once upon a time, Budaörs Airport had served as Hungary’s main international air gateway and was served by many of Europe’s major airlines. However, with no paved runways and little space for growth, the airfield was never particularly suitable and plans for its successor, Budapest Ferihegy Airport were developed only a year after Budaörs Airport opened. Following a short 13-year stint as Budapest’s main airport, in 1950 commercial airline flights migrated to Ferihegy Airport, whilst Budaörs Airport served as a hub for light and utility aviation. Fortunately, whilst the airport may not have seen a ‘real’ airline service for decades, its art deco terminal still stands. Today, this features a rather spartan interior and is almost empty save for some toilets, a few offices and a cafe. Admittedly, given the terminal’s former role, I can’t help but think this could be utilised in a slightly better way, perhaps commemorating Hungarian aviation with a few displays or even a museum.

Today, Budaörs Airport is a popular general aviation hub and for the duration of my stay, all sorts of light aircraft could be seen coming and going, whilst several gliders were operating from a launch point on the other side of the airfield. In addition to this, several pieces of decommissioned military equipment could be seen scattered about, for me the most interesting of which served to be the cluster of Mil Mi-8 helicopters and MiG-21 jets – a number of which seemed to be confusingly wearing the colours of the Belgian Air Component. I am still yet to work out the reasoning for this, however this was slightly strange to see!

At around 0930, an army of volunteers donned in Goldtimer Foundation t-shirts and reflective jackets made their way out to the foundation’s fleet and began prepping each aircraft for a new day of flying, with this set to commence at 1000. As time passed, more and more passengers arrived with a crowd of excited passengers crowding around the Lisunov Li-2’s port wingtip before being led out for their 15 minute flight over Budapest. At almost 1000 on the dot, the two open cockpit aircraft that I would fly on later that morning, the replica Bánhidi Gerle and the Poliparkov Po-2 could be seen taking to the skies in formation before buzzing off into the distance. Meanwhile, once all passengers had been led out to the Lisunov, the cabin door was closed and a short time later its two piston engines fired up into life producing plenty of noise and streams of white smoke that took a while to dissipate.

A short time later, the Lisunov taxied away and made a short journey to the end of one of the airport’s two grass runways before it roared up into the skies of Budapest. With all Goldtimer aircraft bar the Kánya up in the skies, I had another short walk around and watched as two Bell 206 helicopters took off in formation with a load of sightseers. After watching this, I returned to the terminal for a quick toilet stop before waiting for the Lisunov Li-2 to return. As I waited at the fence, I was soon joined by my fellow passengers – with the demographic appearing to be a fair mixture of aviation enthusiasts and sightseers. Soon enough, the roar of the Lisunov’s two engines could be heard before this touched down on the nearmost grass runway, kicking up a fair amount of dust once back on the ground. A few minutes later, this appeared back outside the terminal where it came to a halt before its two engines spooled down and its cargo of happy-looking passengers emerged. Immediately after coming to a halt, several engineers got to work inspecting the aircraft, presumably looking for leaks of any kind, and polishing it to ensure that it would be in a tip-top and photogenic state for its next mission. A minute or so after the last of the inbound passengers had made their way through the fenceline, a Goldtimer volunteer appeared and said a few words in Hungarian, after which all journeyed out to the aircraft.

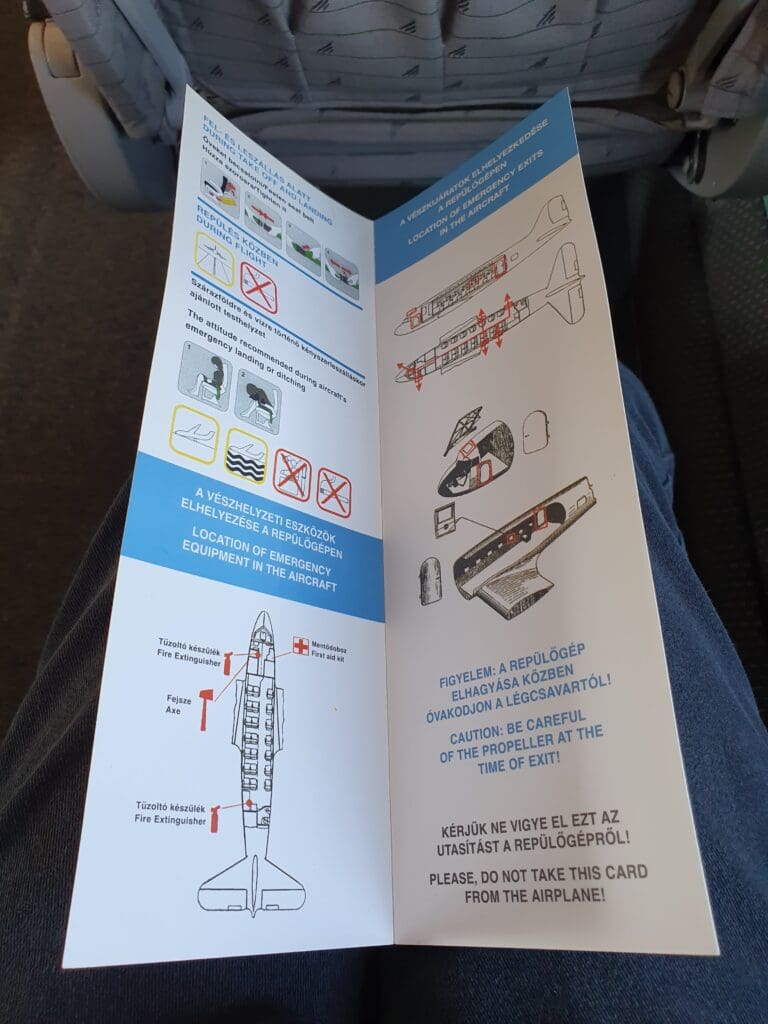

As per the old Soviet-style when the Lisunov Li-2 first took to the skies, that morning passengers were to board the aircraft via the cabin door on the starboard side of the aircraft rather than the usual port side. Making my way around the Lisunov’s nose, with open seating, I decided against spending much time snapping away before boarding. Thus, with little delay, I made my way up the steps that had been positioned up to the aircraft before ducking slightly and entering the aircraft. As I stepped into the spacious area at the rear of the cabin, I was immediately greeted in Hungarian by the very friendly flight attendant, meanwhile to my left two narrow doors could be seen – one leading to the small toilet and the other to the baggage hold.

Comparable in capacity to a BAe Jetstream 31/32, Beechcraft 1900 or Twin Otter, HA-LIX is capable of carrying up to 21 passengers, with seven rows of seats arranged in a 2-1 configuration. Turning right, I began my short uphill ascent and decided to settle one of the single seats in the penultimate row, what would be Seat 6C were the aircraft to have seat numbers. Inside, each seat was comparatively large, well-padded and complete with chunky armrests, and would thus appear rather vintage if fitted to a more ‘standard’ airliner. However, they are far more modern than passengers may expect to see onboard a vintage aircraft. Indeed, these had been installed during the Lisunov’s restoration and had previously been fitted to a Malév Tupolev Tu-134. Each of these seats is covered in a light grey fabric that sports a repeating pattern of darker grey lines and Malév’s motif. Whilst the last Malév service took to the skies in 2012, the cabin remains somewhat of a homage to the defunct national carrier, complete with Malév fabric antimacassars and sick bags. Meanwhile, the sides of the cabin are covered with smart and distinctive green fabric, whilst the ceiling is a cream colour similar to that that you may see in an old train carriage. Up above, each passenger can enjoy the luxury of their own air vent, with these positioned above the large square windows. All-in-all, my first impressions of the cabin were very good, not only was the seat well padded and featured a fantastic amount of legroom, but the cabin seemed to be in a very well-loved and well-maintained state, seemingly less battered than that of the Douglas DC-3 that I had flown on earlier that year.

That morning, all passengers made it onto the aircraft in no time at all and the cabin door was soon closed. In total, just one seat in the passenger cabin would remain free and I was just one of two non-Hungarian passengers on the flight that morning. As soon as the door had been closed, the flight attendant made their way to the front of the aircraft and commenced a speech in Hungarian just as the two Shvetsov ASh-62 engines powered up into life producing plenty of smoke and a fair amount of noise. Following a few moments whilst I assume the pilots went through their checklists, the aircraft commenced its short and bouncy journey over the dry ground to the end of Runway 27L.

Following a short pause during which a bright yellow glider was flung up into the skies, the Lisunov taxied onto the runway before its two piston engines spooled up as plenty of noise and vibrations filled the cabin. Unlike on a modern jet airliner, there was no sensation of being pushed back into your seat as the propliner gently accelerated down Budaörs’ slightly bumpy grass runway. Within a few moments, the tailwheel lifted off the ground and the cabin levelled out before the Lisunov floated upwards into the skies. Skimming the top of the runway as it picked up speed, the Lisunov seemed to cross the perimeter fence at a fairly low altitude before climbing up to 1,800 feet where it remained for most of the flight.

Once the Lisunov was safely in the skies, the flight attendant stood up and continued their speech. As was to be expected given the demographics of the flight, as with the pre-flight speech, this was performed in Hungarian only although I assume this had something to do with the history of the aircraft and our route that morning. Heading northwards after departure, the aircraft passed over the Hungarian capital’s suburban fringes near the city’s border with Pest County before the scenery below changed to fields, hills and forests as we journeyed over the Duna-Ipoly National Park. Below, the wooded hillsides of the national park passed by just a short distance below the aircraft whilst I managed to spot a Scheibe SF-25 motor glider not too far away, perhaps making good use of the plentiful thermals on this very hot summer’s day. However, these thermals did mean that the Lisunov bounced around for much of the flight, leading a fellow passenger in the rear row to let out an occasional gasp.

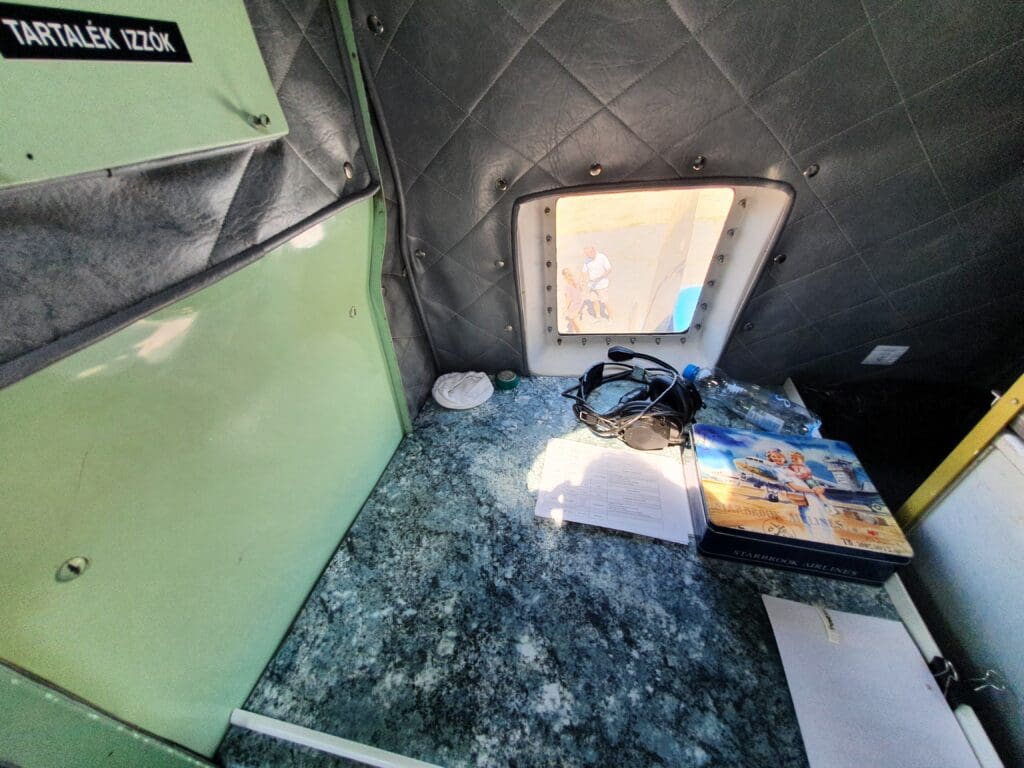

Despite the turbulence, once the flight attendant had concluded their speech, one-by-one passengers were invited to head up to the cockpit, starting with those at the rear of the aircraft. At this time, noticing that I was not Hungarian as they had first thought, the flight attendant very kindly offered to give a summary of their speech in English and asked me if I had any questions about the aircraft. Whilst this was not required, we did have a quick chat about both the Douglas DC-3 and the Lisunov Li-2, and it was clear that the flight attendant was passionate and enthusiastic about their work. Unable to pass on the rare opportunity to head up to the flight deck during a flight, I soon cautiously headed up through the cabin before reaching what could perhaps be described as the avionics bay which sits between the cabin and the cockpit. Proceeding through this, that morning there was a full house in the cockpit, with all four stations there taken. After observing the crew for a few moments whilst they went about their work, I retreated to the cabin just as the aircraft reached its most northerly point on the route where it banked around a castle before heading southwards towards Budapest – although unfortunately I was sat on the wrong side of the aircraft to see this.

From there, the aircraft flew southwards along the Danube as it wended its way towards Budapest and soon the landscape below transitioned from the peaceful countryside of national parks to a mixture of industrial estates and residential areas as we passed the town of Budakalász and reached Budapest’s northern suburbs. A short time later, on the opposite side of the cabin, there was some joyful commotion and plenty of pointing as the historical buildings of central Budapest appeared; however, once again I was sitting on the wrong side for such views, with these primarily taking the form of tower block laden neighbourhoods.

Before I knew it, the flight was nearing its end and the Lisunov crossed the Danube at which point I caught sight of the Groupama Arena, home to local football club Ferencvárosi TC. From there, the aircraft turned to line itself up for an approach to Budaörs’ Runway 27L and the flaps were extended into position. Meanwhile, outside, I caught sight of Kelenföld Station before the scenery turned a little greener as we descended over the green forests and fields that sit to the east of the airfield. Soon enough, the Lisunov whizzed over the perimeter fence and the glider launchpoint appeared. A total of 28 minutes after soaring up into the skies, the Lisunov made a gentle yet bouncy touchdown before decelerating and bouncing around a fair bit whilst several puffs of dirt rose up from the wheels.

Vacating the runway at its end, the Lisunov made its way past the collection of retired military aircraft before reaching the airfield’s hangars. As we neared the terminal, plenty of observers could be seen snapping away at the rare aircraft whilst the next load of passengers waited next to the fence line. After the aircraft had slowly turned around, orienting itself into the west, the engines spooled down and the cabin temporarily fell into silence. At this time, the flight attendant said a few words in Hungarian before advising me that I could take as many photos of the cabin and cockpit as I wished. Taking the flight attendant up on their offer, once the door at the rear of the cabin had been opened and several passengers had disembarked, I made my way up to the front of the aircraft where I admired the aircraft’s Soviet-style green cockpit panels before heading back to the rear of the aircraft. After thanking the flight attendant I headed down the steps and made my way out into the boiling hot summer air.

My Biplane Rides

Whilst my enjoyable Lisunov adventure had come to an end, it was soon time for my next flight of the day, a 15-minute joyride on a Poliparkov Po-2. Following a quick toilet stop, I made myself known at the desk once more before one of their English-speaking volunteers escorted me through the fence line and out to a table where those operating the Goldtimer Foundation’s light aircraft flights that day could be seen waiting for the Gerle and Po-2 to return. Upon arriving there, I was handed a pen and a volunteer pointed and a signature box before giving the command ‘sign’. Whilst I could have been signing up for anything, assuming this to be a mandatory disclaimer, I did so without question and a short time later the Poliparkov Po-2 arrived followed by the Gerle.

Seeing as I would be heading out on the Poliparkov first, once its noisy engine had been shut down and the inbound passenger had disembarked, I walked out to the aircraft along with one of the ground staff. Seeking to partner me with an English-speaking pilot, a new pilot followed me out to the aircraft and the ground staff member informed me that I was in good hands as they were a Wizz Air training captain! Upon reaching the aircraft, I followed the ground crew’s instructions and cautiously lowered myself into the back seat of the aircraft taking care not to cause exorbitant damage to the rare biplane. Whilst expectedly awkward, this was not the most difficult cockpit that I have squeezed myself into and I soon found myself being strapped in by the ground crew – interestingly, the cockpit didn’t seem to have any sort of shoulder harness. The ground crew then placed the Biggles style flying cap and goggles on me and cautioned me not to extend too far out of the cockpit with my camera – having seen this video, I was well aware of the risk and took extra care during the flight.

All ready to go, the ground crew retreated to the end of the wing and the Po-2’s engine noisily fired up into life producing a deafening roar that made hearing air traffic control and anything being said by the pilot completely inaudible. A short time later, the aircraft made its way to the end of Runway 09R before gently taking off into the skies for an extended right-hand circuit around Budaörs Airport.

Once back on the ground, I made my way back to the table where the ground crew could be sitting around and a few minutes later the Gerle taxied up following a fifteen-minute sortie. After the passenger had emerged, I was led out to the aircraft. This time, I would be sitting up front, and the act of actually entering the small cockpit without causing damage proved to be significantly more difficult than on the Po-2. After taking my seat and being strapped in, this time with a shoulder harness included, the engine fired into life on its second attempt, this time producing an equally loud roar before the aircraft made its way onto the runway. Departing from Runway 27L, a shorter taxi was in store and soon enough the Gerle took to the skies.

During this flight, rather than simply undertaking a circuit, we headed out to the hills that sit to the north of the airfield and flew in several circles before heading out over the residential suburbs and turning back towards the airfield. Following another pleasant short flight, the aircraft journeyed around the airfield before making what seemed to be a fairly steep descent and landing on Budaörs’ Runway 09R with a barely noticeable touchdown.

Safely back on Hungarian soil, I made my way back to the terminal for one final toilet stop where another volunteer stopped me and asked me about my experience with Goldtimer. Telling them the truth, I informed them that I had enjoyed three fantastic flights – indeed this was an experience that I would most definitely recommend for any aviation enthusiast!