An Islander Cockpit Ride: Flying Around Scotland’s Hebrides with Hebridean Air Services

Background

When thinking of Scottish airlines in 2021, the first airline that will pop into the minds of most will likely be Loganair. Whilst Loganair’s history dates back to 1962, in recent years their independence from British Airways and Flybe, and subsequent adoption of a uniquely Scottish brand identity, coupled with their growing route network, has assisted in ensuring the carrier is synonymous with Scotland. However at Oban Airport on Scotland’s picturesque western coastline, a lesser-known Scottish airline can be found, Hebridean Air Services who operate a single Britten-Norman Islander. Formed in 1995, as the carrier’s name would suggest, the airline operates a network of ‘lifeline’ flights to a modest number of airports dotted about the Inner Hebrides. From Oban, the airline offers triangular services to Coll and Tiree, and Colonsay and Islay, with Coll and Colonsay sitting untouched by Loganair’s route network. Perhaps rather appropriately given the fact that their sole Islander sports a bright yellow livery, a number of their services are timed to act as a flying school bus, transporting pupils to and from the mainland. Meanwhile, the airline also offers sightseeing options both on their scheduled flights as well as on dedicated thirty-minute sightseer flights. Since 2016, the airline has been owned by the Airtask Group, who also operates an Islander up in the Shetland Islands.

Being an aviation enthusiast passing through Oban, I could hardly pass on the opportunity to fly onboard a rare aircraft type to some of Britain’s smallest and most remote airports that see commercial service. Thus, in June 2021, I had intended to fly on the carrier’s triangular service from Oban to Oban with stops in Coll and Tiree. Unfortunately, the Scottish early summer weather had other plans, and upon showing up at Oban Airport’s terminal, I was advised that the flight had been cancelled. On the plus side, I received a near-immediate refund that was processed by the friendly check-in agent. However, not wanting to give up, I soon got to work planning my next trip up to Scotland to ride on the Hebridean Islander, settling on a trip in early September 2021.

Booking

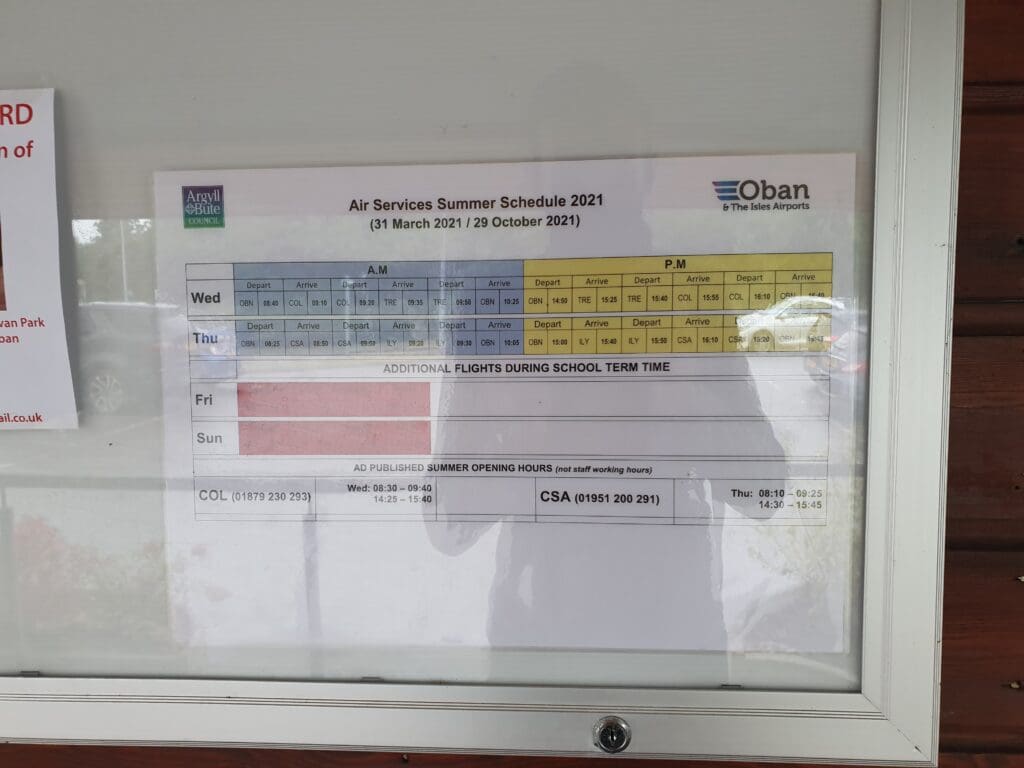

Given Hebridean Air Services’ small size, unsurprisingly tickets for the carrier’s services can only be booked directly with the carrier. Fortunately, with a booking platform on Hebridean Air Services’ website, this is not a particularly difficult task. Whilst some may find it slightly bamboozling, those travelling on any of the airline’s ‘sightseer’ tickets must select Oban in both the ‘from’ and ‘to’ fields of the booking engine. Once this was done, I was then presented with all of the airline’s four sightseeing flight options for that week. These consisted of two round trips from Oban via Tiree and Coll on the Wednesday, a single service to Islay and Colonsay on the Thursday and the much more condensed thirty-minute sightseeing flight on the Friday which does not land. Despite the discrepancies in flight time, each was priced at £80 whilst as per all bookings made with the carrier, these also incurred a £2.50 booking fee.

Once I had selected Thursday’s flight, I was presented with a summary of my choice, which as I had expected, revealed that my flight would head down to Islay before returning to Oban with a quick stop on the small island of Colonsay and would carry the flight number ‘307’. With a total distance of 132 miles, this is Hebridean Air Services’ longest round service and is therefore the best option for those enthusiasts looking to get the most out of their money. Scrolling down, I entered my details before being whisked off to the Trust Payments powered payment page – once all the relevant details had been entered, my money made its way off to the airline within a few seconds and I was presented with a summary of my booking, followed almost immediately by a confirmation email.

The Journey

North Connel Airport sits approximately six miles to the north of Oban’s town centre, and reaching the facility is not a particularly difficult task. For those lacking a car and not wanting to splurge on a taxi, regular bus services operated by local company West Coast Motors connect the town centre with the airport every hour between 0900 and 1500. Rail enthusiasts or those who are simply those looking for a bit more adventure can take one of ScotRail’s services from Oban to Connel Ferry and then make the 25-minute walk across the Connel Bridge to the airport.

With Hebridean Air Services mandating that all passengers arrive at least thirty minutes before their flight’s departure, the only real option for me that afternoon was to take the 1320 bus from Oban to the airport. As it happened, one of the stops for this service was located almost directly opposite the hotel where I was lodging for two nights so I did not have to trundle too far in the light rain showers that afternoon. As I had hoped, at 1322 a red and white bus appeared, and I hopped aboard and told the driver I was headed to the airport. Within a few seconds, I made a contactless payment for £2.30 and received my paper ticket before the bus moved onwards and made its way up the hill and out of the town. From Oban, the bus trundled along the A85 main road, making stops in the villages of Pennyfuir, Dunbeg and Connel, before heading out over the cantilever bridge that spans Loch Etive. After another quick stop, at 1346, the bus pulled up to the bus shelter opposite North Connel Airport’s sole terminal and after thanking the driver I exited the bus at the end of my quick and painless journey.

Sandwiched between the dark blue waters of Ardmucknish Bay and the scenic countryside of the southern portion of the West Highlands, North Connel Airport is by no means one of the more ‘standard’ airports I have visited in the UK. In summer, the airport’s scenic surroundings ensure the airfield is a popular landaway destination for light aircraft pilots across the UK and further afield. Turning to the layout of the airport, the complex features a small terminal with a conjoined control tower and fire station, as well as several hangars that sit parallel to the main runway. Turning to the terminal, having opened in 2008, from the outside this appears to be relatively modern in appearance whilst not deviating too much from local architectural styles.

Having arrived with plenty of time to go before my flight, and seeing as the rain had eased off a little, before heading into the terminal I decided to take a quick walk to get a view of the light aircraft sitting on the ramp that afternoon. Waiting to take to the skies again, I spotted a pair of rain-soaked Socata Trinidads, a GA-7 Cougar that departed off to Perth during my stay, a bright yellow Aeropro Eurofox, and finally a locally based Sky Arrow 650.

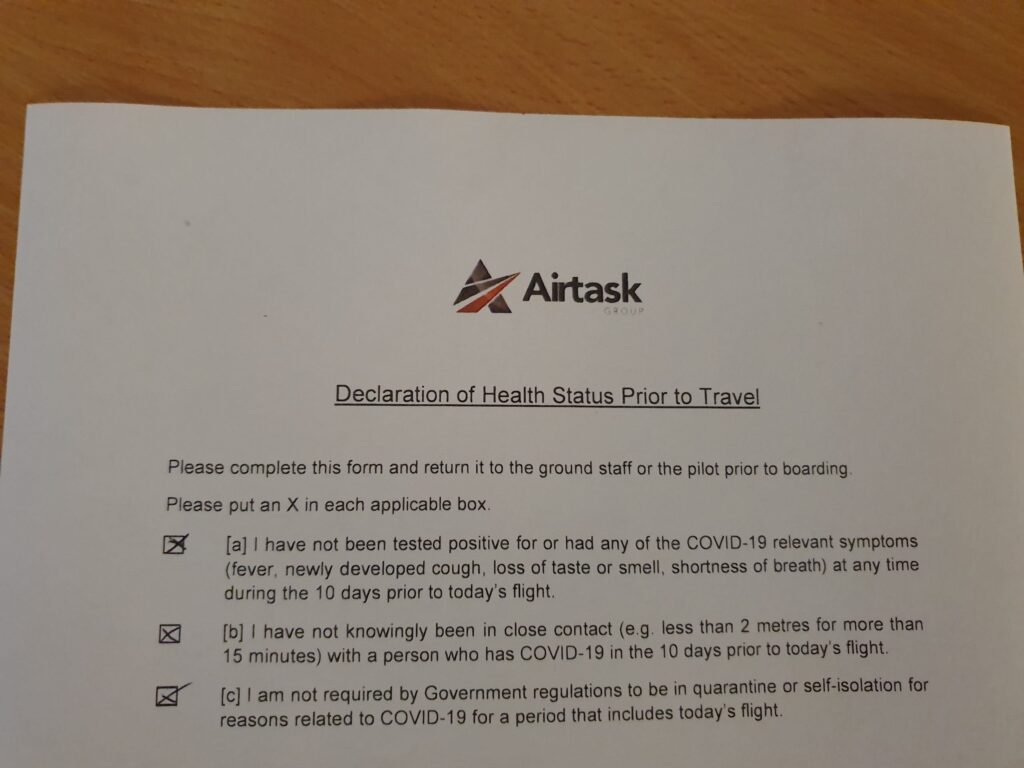

Once suitably soaked, I trundled back to the terminal and as I entered this I received an incredibly friendly and warm greeting from the staff member manning the welcome desk. With this doubling as a check-in desk, the staff member confirmed that I was Mr ‘X’ before informing me that as the weather was not particularly good that afternoon. As I had booked a sightseeing option I could either rebook for the thirty minute sightseeing option several days later or receive a full refund. Explaining that I was an aviation enthusiast and that the experience of flying in the aircraft alone would be sufficient, the staff member happily handed me an Airtask Group Covid declaration form. Once I had filled this in, confirming I had no Covid symptoms, had not to my knowledge come into close contact with a Covid positive person, nor was I supposed to be self-isolating, I handed this back to the staff member. Interestingly, no boarding pass was provided and instead, check-in was completed by the staff member simply informing me that the pilot would appear in fifty minutes or so.

Inside, North Connel Airport’s small terminal is bright and modern, albeit with a slight doctor’s waiting room vibe. With no security check, technically the entire terminal is ‘airside’ and in a rather trustworthy manner, the door to the main apron remained open for the duration of my stay. Examining the interior, this consists of a main waiting area with plenty of comfortable seating – capable of holding far more than the nine passengers that the Islander can carry. I assume this is also used as a private terminal for the occasional visits of executive aircraft to Oban. The decoration is provided through several photographs and paintings of Army Air Corps Apache helicopters, with at least one of these donated by the Wattisham-based 663 Squadron. Later research revealed that the squadron’s helicopters had previously visited the airport whilst training in Scotland.

Whilst lacking a staffed shop or café, a modest range of refreshments could be found in a fridge, next to which sits a hot drinks machine. These were all reasonably priced, whilst payment for these items could be made by means of an honesty box. Meanwhile, three cabinets displayed a range of airport-branded souvenirs, pilot goods and aviation-themed gifts, which were available for sale from the sole staff member in the terminal. Other than the main waiting area, a meeting room could be found featuring a large table and several seats. For those looking to pass the time, complimentary wifi is offered in the terminal which I found to work without a glitch for the duration of my stay. Aviation enthusiasts will be pleased to hear that large windows on one side of the terminal offer views of the apron and runway. Finally, it is worth mentioning that the terminal seemed to be in a spotless and well-cared-for condition. All-in-all, the terminal proved to be more than comfortable for the short wait prior to my flight, whilst the staff member was incredibly friendly, leaving me with no complaints whatsoever about North Connel Airport.

Having been sitting idle on the ground since its morning rotation to Colonsay and Islay, Britten-Norman BN-2B-26 Islander, G-HEBS, could be seen, impossible to miss in its bright yellow colour scheme. Manufactured at Britten-Norman’s factory in Bembridge on the Isle of Wight, this particular aircraft first took to the skies with the test registration G-BUBJ in August 1993. In June 1994, the aircraft headed across the world and began its commercial life in Japan where it flew with Nagasaki Airways as JA5318, and its successor brand, the still active Oriental Air Bridge. During this stage of its life, the Islander was put to work shuttling passengers between the islands of Nagasaki Prefecture. In May 2006, the aircraft was passed on to Air Alpha Aircraft Sales, receiving the Danish registration OY-PHV, before moving onto the US register around a month later before finally re-receiving the registration G-BUBJ in August 2006. In December 2007, the aircraft received the registration G-HEBS and assumed its current role as a true ‘islander’ carrying passengers to, from and in between the islands of Scotland’s Inner Hebrides.

As the flight’s departure time neared, with no one else having entered the terminal since my arrival, it was soon clear that this was to be the first commercial flight that I had ever taken whereby I was the only passenger. With around ten minutes to go until the flight’s scheduled departure time, the pilot appeared, greeted me and gave a brief introduction before walking me over to the aircraft. Whilst the pilot initially offered me the opportunity to sit in what, were the aircraft to have seat numbers, would have been 1B, just behind the cockpit, at the last minute, I was delighted to hear that I was instead offered the opportunity to sit up in the first officer’s seat on the first sector down to Islay.

After snapping some photos, I was instructed by the pilot to remove the chocks from the aircraft’s right wheel – a reminder that this was far from a ‘standard’ commercial flight! I then brought these around to the other side of the fuselage and made my way to the cockpit door near the Islander’s pointy nose. I then stepped up and dived into the cockpit before sliding over to the right-hand side of this and fastening up my shoulder harness. Following me, the pilot then slithered up into the cockpit and promptly made a remark about the Islander’s small cockpit size; nevertheless, this offered an abundance of room compared to the cockpits of the light aircraft that I was somewhat more used to flying. Turning to the control panel, given the Islander’s age one may expect this to feature analog gauges galore. For the most part, this was true, except for a retrofitted digital attitude indicator and a Garmin GPS.

Once the pilot had completed several pieces of paperwork, they slammed the cockpit door shut and I was handed a headset and advised to plug this into the two ports located to the right of the main panel. Without any delay, the pilot went through the quick start-up sequence and the two Lycoming O-540 E4C5 piston engines roared into life one by one, after which the flaps were partially lowered in preparation for our departure. Seeing as I was wearing a noise-cancelling headset, the start-up process seemed to be a fairly quiet affair, although the true noise of these engines became clear during the following two sectors.

After the engines fired up into life, the pilot spent a couple of minutes or so running through several checks before inputting Islay Airport’s ICAO code, EGPI, into the Garmin GPS – revealing this to be 55.4 nautical miles to our south. However, the flight would be flown visually with the GPS track there for reference. Once done, the pilot contacted North Connel’s tower with the callsign ‘Golf Bravo Sierra’ and reassuringly informed the local air traffic control that our endurance was three hours before the Islander quickly lurched out of its stand.

From our starting position, the Islander arrived at North Connel’s runway in a matter of seconds. With few passengers and no cargo, the aircraft may have been able to make a successful takeoff from the intersection however following procedures, the pilot turned the aircraft right and the Islander made a quick backtrack to the end of Runway 19 before turning around. At 1459, one minute ahead of the Islay flight’s scheduled departure time, the pilot pushed the two round power levers fully forward and the aircraft accelerated down the runway before gently floating upwards at around 70 knots.

Seconds after taking to the skies, the Islander crossed the mouth of Loch Etive and continued to fly in a straight line, reaching Oban a couple of minutes later where clear views of the town’s harbour were offered. There, whilst not wearing my glasses I managed to make out the hotel where I had been staying, as well as the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry, the MV Isle of Mull that had just arrived from Craignure. As the Islander gently cut across the town, the aircraft settled at its cruising altitude of 1,600 feet and the altitude and heading functions of the autopilot were switched on.

Bumbling southwards at a speed of 120 knots, with the propellers whirling at 2,500 revolutions per minute, the Islander’s flight took it along the south of the Isle of Kerrera, with this on the starboard side of the aircraft and the mainland on the other. In the cockpit, little radio chatter could be heard on Scottish Information and I chatted to the friendly pilot about the joys and challenges of flying in Scotland, their favourite aircraft and the Islander.

Turning my attention back outside, the Islander continued to fly parallel to the rocky coastline of Argyll’s mainland whilst a selection of the Inner Hebrides’ Slate Islands appeared both ahead and to our right. As we flew southwards, the distinctive miniscule island of Easdale, home to fewer than sixty residents appeared whilst Luing could be seen passing by to the left of the aircraft. From there, good views of the large yet uninhabited islands of Lunga and Scarba soon approached on the right-hand side. Seeing as the flight was ahead of schedule and making good progress, and given my status as a sightseeing passenger, the pilot opted to make a slight detour over the Gulf of Corryvreckan, famous for its standing waves and whirlpools. After performing a semi-circle around a large whirlpool, the aircraft continued back on its course towards Islay, heading down the western side of one of Scotland’s largest islands, sparsely populated Jura.

At 1520, the northern tip of Islay and its 45-metre-tall Ruvaal Lighthouse appeared. Once the domain of a lonely lighthouse keeper, this now automated lighthouse has been in operation since 1859. From there, the aircraft descended in an attempt to keep out of the thick clouds and the pilot soon contacted Islay’s air traffic control tower. After flying parallel with the coastline over the Sound of Islay for a couple of minutes, the aircraft crossed the coast near the village of Bunnahabhain. From there, the views of the choppy dark blue sea were replaced by a mixture of wild rocky moorland and forests, with an increasing number of farms and buildings visible as the Islander trundled towards the southern half of the island.

As the Islander neared Islay Airport, the visibility dropped rather suddenly as the aircraft entered a rainshower that was hovering around the airport that afternoon. At this point, the first lumps and bumps of the flight could be felt although these were only relatively minor and did not cause any concern for myself, and thankfully the pilot! Flying downwind for an approach to Islay’s Runway 08, the aircraft crossed over the coastline again and headed out over Laggan Bay before turning onto the base leg. At this point, the flaps were lowered and the aircraft decelerated with some vigour before the airport emerged suddenly through the mist.

Performing a sharp turn to place the Islander onto its final approach, the aircraft darted down towards the runway and at 1530, 31 minutes after leaving Oban, the aircraft returned to earth with a gentle bump. Despite landing on the shorter of Islay Airport’s two runways, at 635 metres long this proved no challenge for the rugged STOL-capable prop and the aircraft slowed gently. To the right, Islay’s terminal could be seen – which, whilst not large, far outsized that of North Connel. At that time, no other aircraft could be seen on the ground, with three other movements that day – the Saab 340 operated Loganair morning and evening services to and from Glasgow, and the morning Hebridean Air Services flight.

Having expected the Islander to turn right and taxi off to the terminal, to my surprise once at the end of the runway this vacated to the left and made its way over to a gate at the northern tip of the airport where a small portacabin and car park could be seen. There, a single ramp worker as well as a small group of passengers could be seen waiting to greet the inbound aircraft. Moments later, the aircraft came to a gentle halt and the two engines spooled down bringing an end to my exciting cockpit ride – the first time I have ever had such an experience onboard a commercial flight!

As soon as the propellers stopped spinning, the ramp worker-led passengers out to the aircraft and once the pilot filled out more paperwork, complaining about this in the process, the cockpit door was opened and I slid out and joined my fellow passengers. A total of four new passengers, consisting of two middle-aged couples, would be joining at Islay. It turned out that these passengers were daytrippers who had taken the morning flight down and were returning to Oban with Islay’s most famous export, whiskey. At the rear of the aircraft, the pilot cautiously placed the passengers’ whiskey-laden bags in the luggage hold at the rear of the aircraft, making friendly and lighthearted conversation with the passengers whilst doing this. Once two of the passengers had slid into the rearmost row, I was advised by the pilot to take my seat in the second to rearmost row. Taking extreme care not to bang my head, I stepped into the cabin and slid over into what, were the aircraft to have formal seat numbers, would have been Seat 3B. Meanwhile, the other two lucky passengers were assigned Seats 1A and B behind the pilot – separated from the cockpit by a temporary plastic screen to minimise contact between the pilot and passengers.

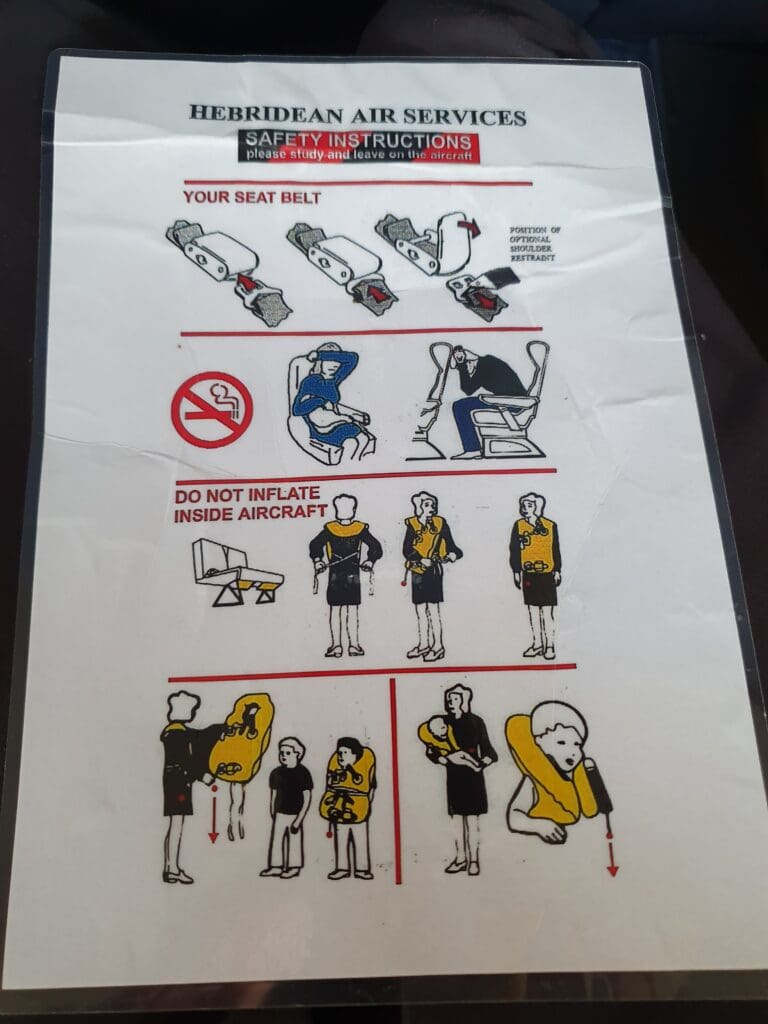

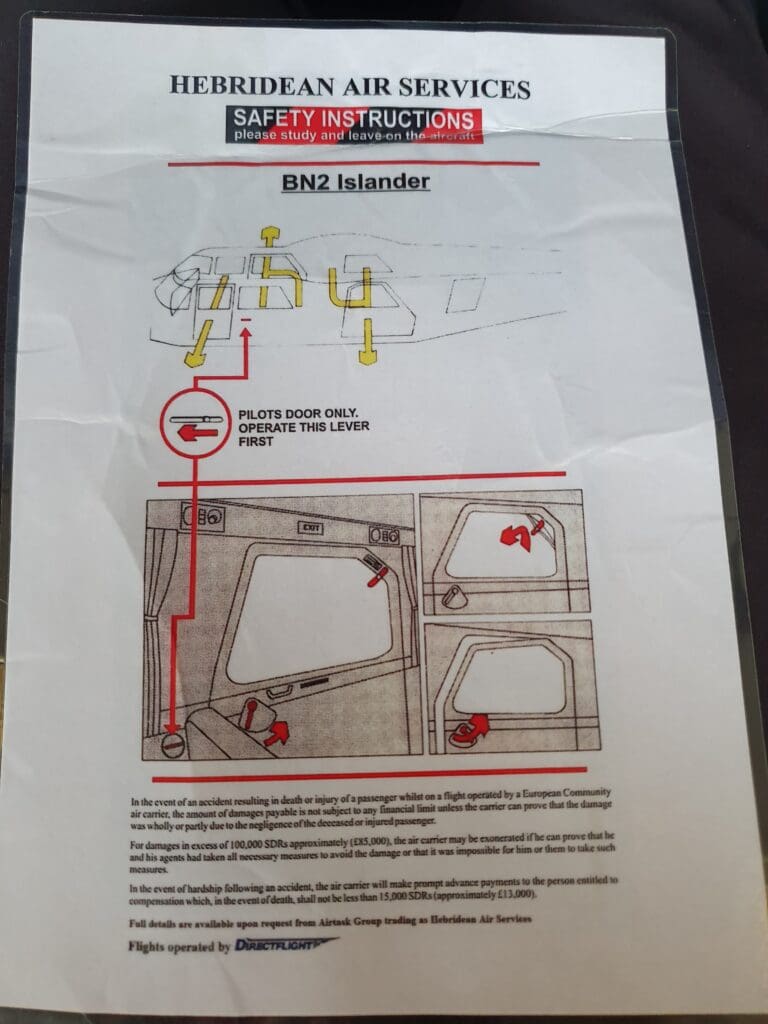

Onboard, the Islander’s passenger cabin consists of four rows of conjoined blue leather seats – to my surprise these provided a decent amount of legroom and were more comfortable than your typical low cost airline ironing board seat. Despite the aircraft’s age and the rugged nature of its operations, the area around my seat appeared to be largely free of any notable signs of wear and tear, with only a few scratches on the plastic panelling and metal seat belt. Meanwhile, both the seat and the blue carpet below appeared to be mostly clean. Above, as on a larger airliner, both air vents and reading lights could be seen although neither of these appeared to work. Turning to the seatback pocket, this contained a dog-eared safety card, two sets of disposable earplugs, an unbranded and battered but thankfully unused sick bag as well as a zip lock bag which I assume was there to store the sick bag in the event of its use. Perhaps capable of fostering some concern amongst nervous passengers, the safety card featured a note regarding insurance payments in the event of an accident!

As soon as I sat down, the cabin door to my left was slammed shut and the pilot made their way to the cockpit. Without any briefing or safety speech, the pilot fired up the Islander’s two noisy Lycoming piston engines whilst the flaps were partially extended. A few moments later, the aircraft began a quick taxi and soon reached the end of Runway 26, backtracking down this before performing a u-turn to point the aircraft into the wind. Following a nine-minute stay on Islay, at 1539 the Islander’s cabin rattled and filled with noise as the aircraft commenced another gentle take-off roll before steadily rising up into the cloudy skies.

Almost immediately after leaving the ground, the aircraft banked to the left and rolled out on a northerly heading that would take the aircraft straight up to Colonsay. With low-lying clouds all around, the aircraft appeared to hug the ground in order to keep out of these. Whilst unable to see the altimeter on this sector, my usually accurate GPS tracker displayed the aircraft as levelling off at a very low cruising altitude of just 500 feet. This allowed for good views of Islay’s green fields and villages as these rapidly whizzed by beneath the aircraft.

A short while after departure, the Islander crossed Islay’s Loch Indaal, after which the landscape became much wilder with far fewer farms and settlements to be seen below as the aircraft made its way north towards the Islay coastline. Approximately seven minutes after departure, the Islander crossed a deserted sandy beach near the village of Killinallan and journeyed over the blue waters of the North Atlantic, the northern tip of Islay remaining visible to the east of the aircraft.

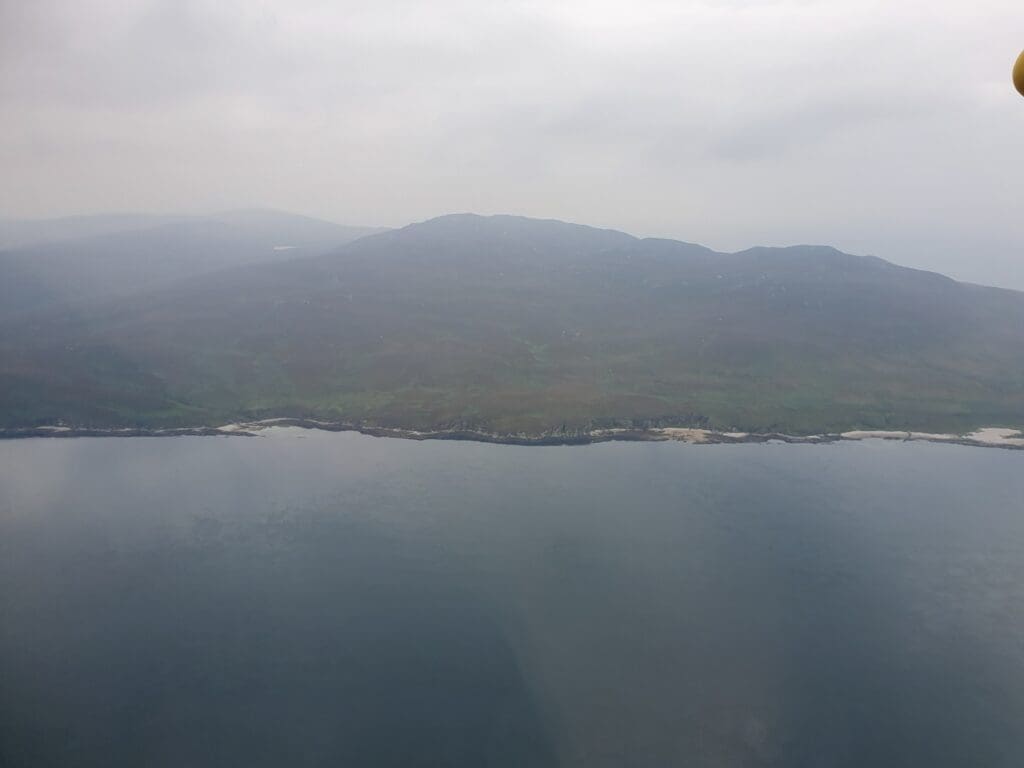

A total of ten minutes after leaving Islay, the jagged rocks and picturesque turquoise waters at the southern tip of Oronsay appeared. Sitting to the south of Colonsay, as of the latest survey in 2011, this small island is home to a total of eight residents. As we flew over this, Oronsay Priory, the island’s historic monastery that was first established in 1353 appeared, surrounded by several fields. This was then replaced by several rocky outcrops before the Islander made the short crossing over to the larger island of Colonsay.

Flying over the south of the island, the only signs of life that could be seen were several herds of sheep and I failed to spot any buildings, roads or tracks in the rough and rugged landscape below. Soon enough, the aircraft crossed another bay filled with turquoise water more typically associated with warmer climes at which point the flaps were lowered, indicating our imminent arrival. Moments later, the aircraft banked to position itself for a landing on Colonsay’s Runway 11.

Seconds after shooting over a dirt road and the airport’s perimeter fence, the Islander performed a bumpy touchdown on the airport’s short 501-metre-long runway at 1552, ending our short thirteen minute hop up from Islay. Quickly decelerating, the Islander soon taxied left off the runway and arrived at the small circular-shaped ramp almost immediately. There, the airport’s sole fire engine could be seen waiting just in case this was needed, standing outside the minuscule yet modern terminal. Once the aircraft came to a full stop, the engines powered down and the cabin fell into total silence. With around 25 minutes to go until the flight’s scheduled departure time for its final leg back up to Oban, the pilot turned around and informed all onboard that he would return in ten to fifteen minutes.

As we waited inside the aircraft, the cabin became somewhat stuffy and a little hot, with those passengers behind me discussing amongst themselves whether they would get into trouble if they opened the rear door – eventually concluding that this was a bad idea. True to his word, after fifteen minutes the pilot reappeared with a single passenger in tow. Opening the rear cabin door, the new passenger was placed next to me and the row in classic Soviet airliner style, the row in front was lowered in order to allow for extra space.

Once the cabin door was closed, the pilot returned to the cockpit, and, as had been the case at Islay, nothing by means of a welcome or safety speech was performed prior to the start-up of the Islander’s noisy piston engines. After these powered up, the aircraft began its taxi over to the airfield’s short and narrow runway. Arriving there in a matter of seconds, the aircraft then backtracked before performing yet another rattling and noisy takeoff roll before soon rotating up into the cloudy skies.

As the Islander climbed up to its cruising altitude of 1,400 feet, several fields near the airport came into view, with these surrounded by Colonsay’s wild and rocky landscape. Speeding towards the coast, the Lord Colonsay monument soon appeared. Erected in 1879, this serves as a tribute to Oronsay born Duncan McNeill. This was almost immediately followed by the island’s main settlement, the small village of Scalasaig. There, clear views of the island’s harbour could be seen, alongside the Caledonian MacBrayne ferry terminal – the latter appearing to be empty with the day’s service to Oban having already departed.

After passing Scalasaig, the aircraft headed out over the sea, with the island remaining in view off the left side of the aircraft. Sitting on the right hand side of the cabin, little could be seen at this point with the exception of the island’s fish farm – this having made national news in early 2020 when almost 75,000 salmon escaped following Storm Brendan. Eleven minutes after leaving Colonsay, a collection of the Slate Islands appeared once again to the east. From there, more and more islands appeared whilst the mountainous shores of the mainland could also be seen as the Islanded made its way northeast towards Oban.

At 1628, the rocky western shores of the Isle of Kererra appeared, with good views of the entire island offered before Oban popped into view indicating our imminent arrival. Crossing the mouth of the harbour, good views of the entire town and its shoreline were offered before the aircraft commenced its descent over the villages and forests that separate Oban from Connel.

With minimal turning, the flaps were extended and the aircraft continued to sink, soon turning onto finals for North Connel Airport’s Runway 01. As the aircraft crossed Loch Etive, the Connel Bridge could be briefly seen and before I knew it the aircraft was diving down to the runway before performing a gentle touchdown at 1632 and quickly decelerating in order to avoid any backtracking before exiting the runway.

Taxying off this, the Islander returned to the same stand from where we had departed and the engines were promptly spooled down. With no ground crew appearing to meet the inbound flight, as soon as the engines’ propellers stopped whirling, the pilot disembarked and opened both the front and rear passenger doors. Assisting passengers out of the aircraft and retrieving their bags from the small hold at the rear of the fuselage, as I exited the Islander, I thanked the pilot for the ride and made my short way over into the terminal. Upon entering the terminal, I was warmly welcomed back to Oban by the staff member in the terminal.

Conclusion

Having never flown on an Islander before, I was pleasantly surprised by how comfortable the aircraft was, although as expected this was incredibly noisy and rattled with some ferocity for the majority of my three flights. Turning to Hebridean Air Services, I am unable to say anything bad about the airline! The two staff members I interacted with were incredibly pleasant and friendly, not to mention my once-in-a-lifetime cockpit ride on the sector down to Oban! Even if you’re not lucky enough to be placed in the cockpit, I would say this is a must for those who find themselves in Oban and was most certainly £82.50 well spent.